The Purpose of Equine Osteopathy

The career of sport horses being longer and longer, and the well-being of the horse being widely put forward for several years, more and more horse owners call upon an equine osteopath. Let’s take a closer look at the basics of equine osteopathy, how it works and its benefits.

Table des matières

💡Did you know?

Let’s start with a little anecdote: France is the country in the world with the highest density of osteopaths (human) with one osteopath per 1930 inhabitants. France also has an extremely high density of animal osteopaths with currently 380 osteopathic veterinarians, and more than 1000 animal osteopaths (not all of whom are yet registered in the national register of aptitude). This represents one animal osteopath for 630 horses.

The founding principles of osteopathy

Osteopathy is a manual therapy that was “founded” in the 19th century by an American physician named Andrew Taylor Still. The definition of the union of osteopaths in France is as follows:

Osteopathy is a manual therapeutic method that focuses on identifying and treating mobility restrictions that can affect all structures in the (human) body. Any loss of mobility of the joints, muscles, ligaments or viscera can cause an imbalance in health.

It is a technique that was recognized by the WHO in 2000. All its functioning is based on fundamental principles determined by A.T. Still. Let us quote 3 of them:

- notion of unity of the body: the body is a whole

- notion of homeostasis: the body must be in balance on all levels, otherwise it is “the disease”.

- rule of the artery: the good vascularization of the structures and the body is essential for a good functioning.

An osteopath’s role is to restore the maximum mobility and balance to the body, thus restoring its natural harmony, so that everything functions properly.

Notion of unity of the body applied to the horse

This notion of “unity of the body” implies that the body is a whole and that it cannot be separated into blocks. The osteopath therefore has a global approach to his patient (human or animal). He takes into account the phenomena of compensation that can be created following a pain.

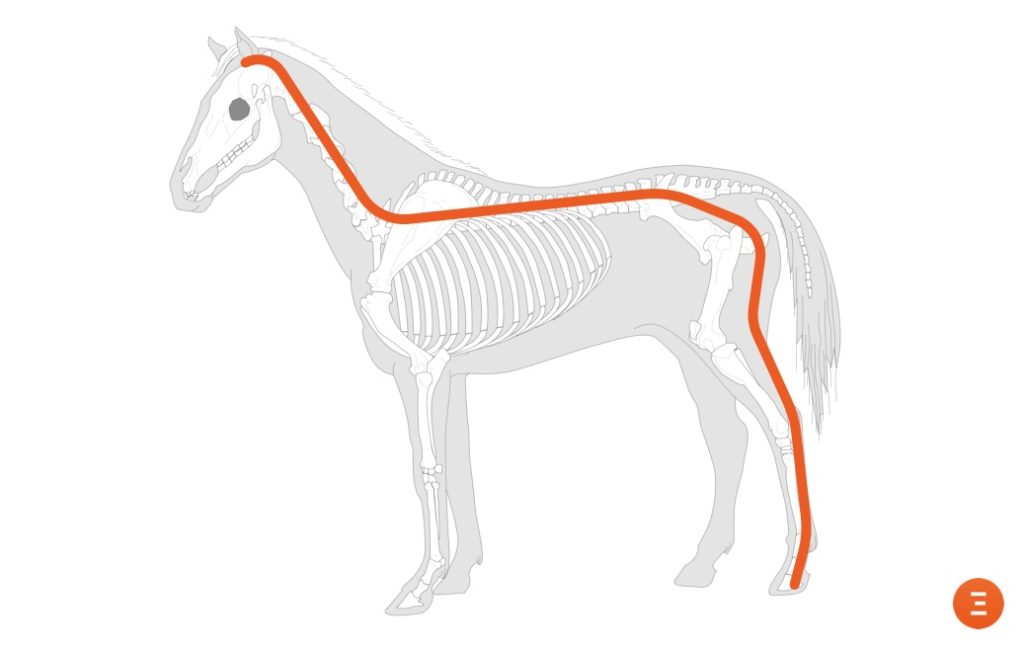

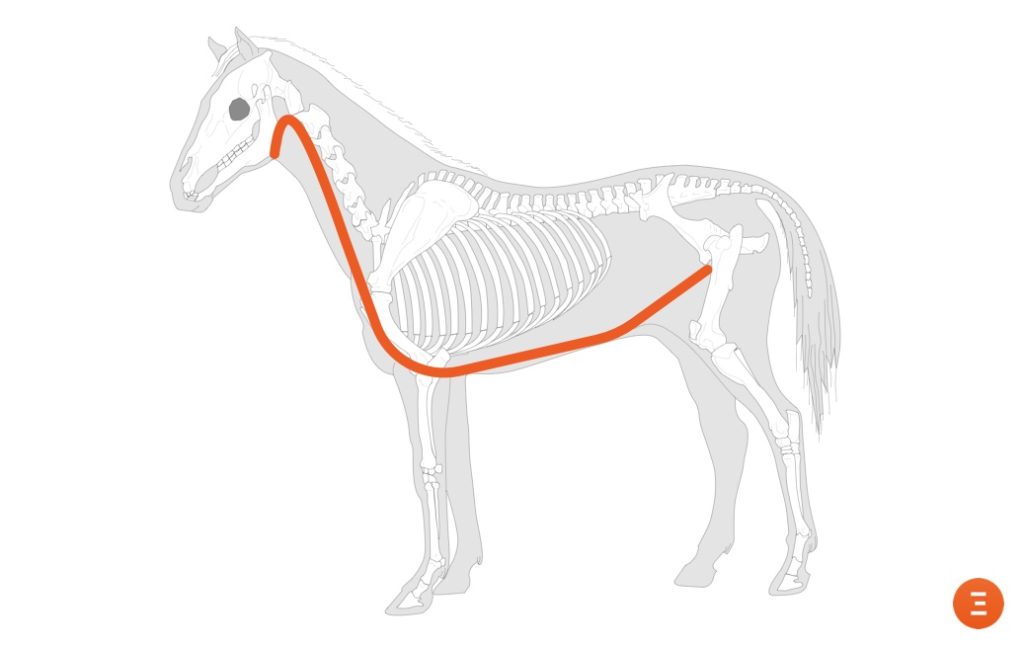

The myofascial chains and other links between structures

The existence of myofascial chains (connecting muscles to fascia) has been scientifically demonstrated in horses (Elbrond & Schultz, 2021), through dissections. This explains the link between different structures, sometimes distant like the link between the mouth or the neck with much deeper structures like the heart, the stomach, the diaphragm or the Psoas Iliaca muscle.

In particular, there are so-called central fascial chains which also explain why a dental occlusion problem will have an impact on the hindquarters as we already explained in our article dedicated to the tightening of the noseband.

A link between viscera and muscles has also been proven. Isabelle Burgaud, in her webconference, explains that the viscera are attached to the spine by fascias (visceral ligaments), “like hangers on a bar”. This means that the viscera will pull the spine down. Thus, painful or overly heavy viscera can lead to dysfunction in the spine.

In the same way, viscera with each other can create chains of reactions. If we take the example of the stomach, it is attached to the liver, to the spleen by the gastro-splenic ligament and to the diaphragm by the gastro-phrenic ligament. So any strain on the diaphragm is going to impact the stomach, and any stomach problem is likely to impact the diaphragm, liver and spleen!

Finally, there is also a nerve and vascular connection, so if there is compression or stretching of the vessels or nerves at the “hangers” we were just talking about, it will impact the function of the viscera.

Where do osteopathic dysfunctions in horses come from?

Osteopathic dysfunctions in horses often come from unexpected traumas, for which the body has not been able to prepare itself (fall, wrong movement, avoidance reactions following a bad jump or a bad landing). It can also come from the repetition of an abnormal movement, such as a chronic lameness for example.

Growth, problems with teeth, harnessing, growth, stress can all be sources of dysfunctions that require the intervention of an equine osteopath.

The truth about “displaced vertebrae”

One of the most well-known osteopathic dysfunctions is the so-called “displaced vertebra”. It is important to understand that this is not a true displacement of the vertebra. If it were, the spinal cord (which runs down the center of the vertebra) would be compressed or severed: the horse would then be paraplegic or quadriplegic. This is a far cry from that.

What’s really happening is that the little deep muscles (postural muscle) that allow the vertebrae to move relative to each other are going to be stiff, contracted. Thus, the vertebra can no longer move properly in all 3 directions of space. This can result in a small “irritation” of the nerve that exits the vertebra at that point. Consequently, the structure innervated by that nerve will then receive “inflammatory” information, which can therefore create various dysfunctions on very distant and very deep structures that have, a priori, no direct link with the original cause.

The connection may be the opposite, that is, an inflammatory viscera may create a blockage on the vertebra to which it is connected.

What is the role of the equine osteopath?

The notion of body unity thus explains the chains of compensations and osteopathic dysfunctions that occur after a traumatic event or after a pathology. The osteopath’s role will then be to reassemble all the tracks of these dysfunctions to get to the source problem, like a detective analyzing all the clues to find the culprit.

During the first few sessions, the osteopath’s mission will be to address compensatory dysfunctions so that he or she can gradually work his way back to the source problem. This may require several sessions close together (at least 3 weeks – 1 month between sessions).

Beware, the osteopath sometimes cannot intervene. Indeed, at the beginning of the session, the osteopath will have to make what is called an opportunity or exclusion diagnosis, aiming to exclude any veterinary emergency prior to osteopathic treatment. It may therefore be necessary to bring in the veterinarian first, and then the osteopath at a later time.

Inversely, having the vet only will certainly address the root cause of the problem but not necessarily the compensations that have set in.

Have the effects of equine osteopathy been proven?

Yes, the impact on the horse’s locomotion has been objectivized in a study published in 2013 (Burgaud et al., 2013). The study shows on the group of young horses, a rapid and significant improvement of the elevation and symmetry in the 10 days following the osteopathic treatment. This improvement persists for at least 20 days.

In older horses, it takes longer for the horse to rebalance: the effects can be seen between 3 and 5 weeks after treatment. Therefore, this time frame should be taken into account for the competition season.

As the osteopath acts on the horse’s postural pattern, the horse will need a few days to reacquaint itself with his new sensations. The horse is likely to be very sore in this period. This is why following a session, the osteopath usually asks that the horse be walked in hand.

A lameness may in fact appear after a consultation. The lifting of muscle compensations may bring out an underlying osteoarthritis pain. This will therefore need to be treated appropriately.

Should you choose a veterinary osteopath or an animal osteopath (not a veterinarian)?

This choice is actually all yours.

The advantage that osteopathic veterinarians have is that they can use all the tools of both trainings. The overall vision and the global consideration of the body that osteopathy has, but also the X-rays, the MRI, blood tests of the veterinary arsenal. Depending on the case, he will be able to choose to treat your horse according to techniques specific to the veterinarian, or to the osteopath.

The National Register of Competence of Animal Osteopaths

This part is only valid for France. Please check the regulations for different countries.

Since 2017, the order of veterinarians has set up a system of regulation to ensure the competence of osteopaths who are “non veterinarians”. This regulation thus passes through a national aptitude exam with a theoretical part and a practical part. Animal osteopaths who have passed this exam are then registered in the National Register of Aptitude. Practitioners not registered with the NRA are subject to prosecution for illegal practice of veterinary medicine.

Passing this exam is, by the way, mandatory, even for practitioners already set up in osteopathy and Shiatsu before 2017.

Don’t panic if your regular equine osteopath is not currently on the registry. There are currently 250 people on the ANR, but 750 practitioners are waiting to take the exam, the delay having been caused by the Covid crisis.

Thingd to remember

Osteopathy is a manual technique that has the particularity of taking the patient’s body as a whole. Indeed, all structures are linked together by chains whose existence has been scientifically demonstrated.

Osteopathic dysfunctions are not lesions as such but blockages or restrictions of mobilities. These are related in particular to deep muscle spasms.

The osteopath acts on the chains of compensations that are put in place following a trauma or an emotional shock. Ostheopathy’s effects on the horse’s locomotion have been proven. The technique is particularly effective on young horses.

See you soon for a new article,

Camille Saute

Co-founder of Equisense and R&D manager

Bibliography

Burgaud, I. (2021). Ostéopathie chez le cheval de sport, pourquoi et comment Webconférence Ifce.

Lussot Kervern, I., & Salabert, M. (2021). Ostéopathie animale et vétérinaire : état des lieux. Webconférence Ifce.

Biau, S., & Bouloc, C. (2017). Prise en charge ostéopathique en équitation. Equipedia.

Burgaud, I., Biau, S., Aujol, K., & al (2013). Impacts d’un traitement ostéopathique sur la locomotion du cheval de sport en liberté. Pratique Vétérinaire Equine, 45(178), 45–53.

Elbrønd, V. S., & Schultz, R. M. (2021). Deep Myofascial Kinetic Lines in Horses, Comparative Dissection Studies Derived from Humans. Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 11(01), 14–40.